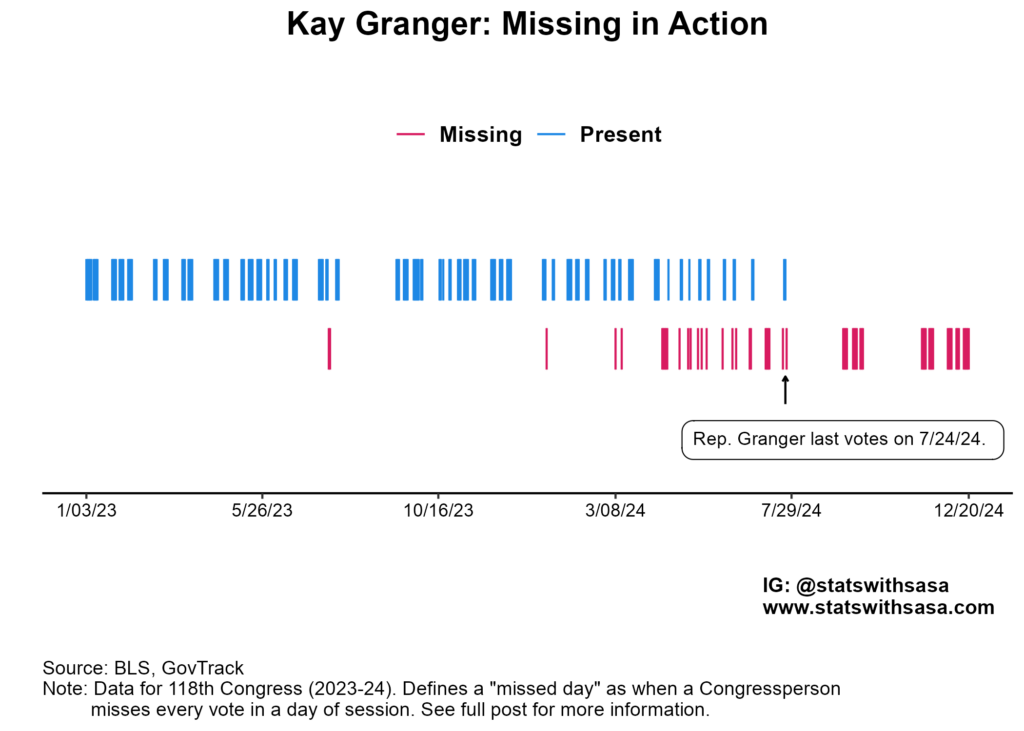

This December, a local publication shockingly revealed that Rep. Kay Granger (R-TX) had been missing for five months. She cast her last vote in July, and disappeared thereafter. It took five months for the public to recognize and call this out, after which her family admitted that she had been secretly living in a dementia care facility.

Rep. Granger wasn’t a nobody, either — she chaired the House Appropriations Committee as late as April 2023. The fact that it took five months for anyone to notice this is appalling. As many have noted, the whole fiasco speaks to some troubling norms around Congress and its attendance issues.

This news pairs nicely with renewed GOP efforts to get federal workers back to the office (offices which may or may not exist, by the way). It all begs the question:

How often are Congress members absent from session?

Truly getting to the bottom of this question is a tricky. Neither the House nor Senate takes attendance during their sessions. Technically, quorum votes measure attendance, but they are infrequent (about once or twice per session).

So for this analysis, I pulled voting data from the current 118th Congress (2023-2024) . During a vote, members typically vote “Yea” or “Nay”. A member who is present during the vote but wants to abstain can vote “Present”. Members who are absent or chose to not vote at all are recorded as “Not Voting”.

Congress doesn’t vote on every day of session, but there are also days with many votes on different issues. Thus, for any given member of Congress, we can roughly keep track of absences by noting days where votes were held, but that member was recorded as “Not Voting” on every vote. See here for more information on my methodology.

Importantly, this analysis only considers absences during session. Congress doesn’t meet all year, and members are given ample breaks. In 2024, the Senate met for 130 days. In comparison, most Americans work 260 days a year (52 weeks*5 days). So this analysis doesn’t even account for the ~130 days “off” that Congress already gets every year from session.

Click below to skip to any section of this article:

Consecutive Missed Days

Since this conversation was sparked by Rep. Kay Granger completely disappearing for five months, let’s begin by looking at the longest consecutive absences of any member of Congress. Since our proxy for absences only works on days when votes are held, I look at the consecutive missed days of voting, and measure that. The actual calendar length of that absence could be much longer. For example, Rep. Granger was missing for ~150 calendar days. However, votes were only held on 32 of those days. So her absence is measured as “32 consecutive missed voting days”. Let’s look at some of the other worst offenders on this front:

This chart reveals something stark — Rep. Granger did not have the longest absence in the 118th Congress. Raul Grijalva (D-AZ) missed 71 consecutive voting days from Feb. 2nd to Nov. 11th (265 calendar days). Rep. Grjivala has cancer, and I am of course sympathetic to that. However, he has missed over 400 votes in that time, and he clearly should have stepped down much earlier to take care of his own health. Instead, he enjoys a $174,000 salary, compared to a median household income of $61,000 in his district. And his 811,000 constituents have essentially been without a voice in the House of Representatives all year.

This chart only lists the top 10 worst lawmakers’ consecutive absences. In comparison, I note that the average American only gets 15 days of PTO after 5 years of service at a company. And it’s not really even a fair comparison. After all, the chart only gives voting days missed and only assesses consecutive absences, not the total amount missed during a year. And the actual calendar length of the absence is longer.

So for a more apple-to-apples to comparison, let’s look at total absence rates for the 118th Congress.

Total Missed Days

Since the 118th Congress has been meeting for two years, I now consider the absence rate for the chart below, which I define as (voting days missed)/(total voting days). I use a cutoff of 10%, which would be analogous to an average American taking 26 days off in any given year. According to the BLS, after 5 years at a company, the average American receives 15 PTO days and 8 paid sick days for a total of 23 paid days off every year.

You read that right, 44 members of Congress (~1 in 12) are taking time off at a higher rate than the average American. That’s despite being well compensated ($174k/yr). Not to mention that serving as a Representative or Senator is one of the highest and most important honors an American can hold. It’s also voluntary — no one is forcing these people to serve.

Ultimately, this is sacred duty that should be taken seriously. Each member is responsible for hundreds of thousands, even millions, of constituents. I don’t think anyone would disagree that they should be held to a higher standard than the average American. Instead, dozens of them are ostensibly treating this responsibility lackadaisically.

Worst Offenders

Of those 44 members who are absent >10% of the time, some of them are worse than others. Let’s take a look at the worst offenders of the 118th Congress.

Some of these names might not be surprising. A lot of Congress is old or sick. Like I mentioned, Rep. Grijalva has cancer. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee died in office after battling pancreatic cancer. But again, serving in Congress is totally voluntary. Stepping down is always an option when someone realizes they are no longer fit to serve, and we have designed measures to replace those who resign or die while in office. By chronically missing votes for legislation, these members are depriving millions of Americans the opportunity to be properly represented in Congress.

Let’s wrap up with a case study that helps better visualize the absenteeism problem in Congress.

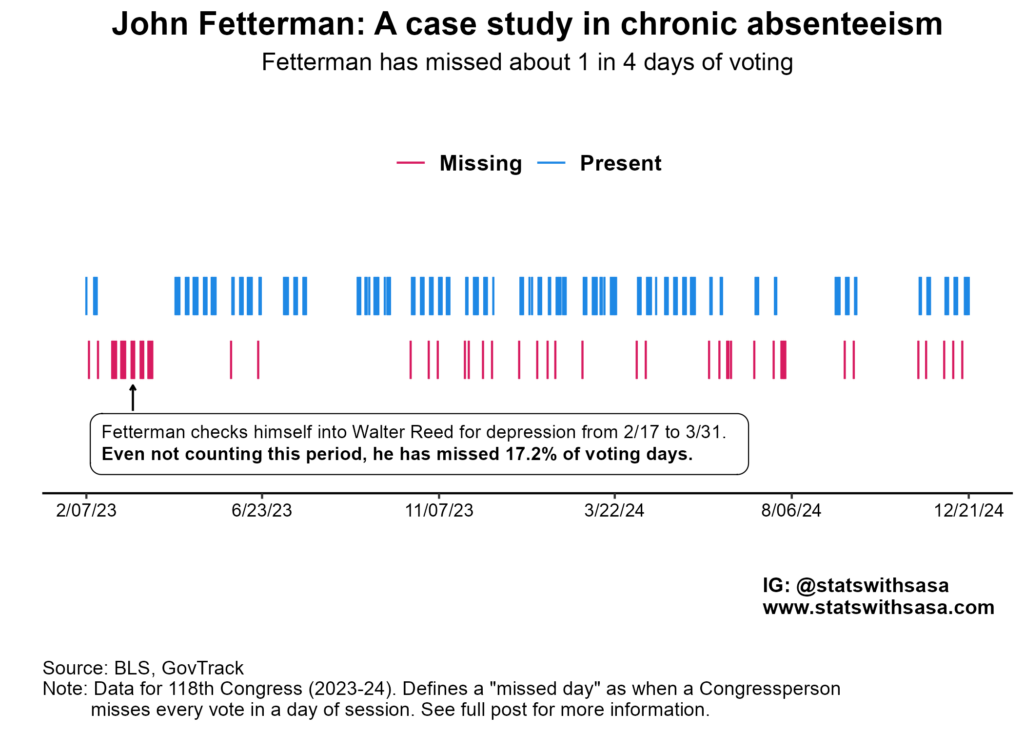

John Fetterman: A case study in chronic absenteeism

This case study focuses on John Fetterman. Unlike the other “worst offenders” listed above, he’s relatively young at 55. He’s also a freshman Senator with a lot to prove, and doesn’t already have the long, storied, and accomplished careers of people like Rep. Jackson Lee. Furthermore, he was not on a presidential ticket like Rep. Phillips or Sen. Vance. Sen. Fetterman did suffer a stroke relatively recently, but that was before being elected and getting “locked in” as Senator.

John Fetterman has missed roughly 1 in 4 days of voting, despite being a freshman Senator. He did briefly check himself into Walter Reed to get treatment for depression shortly after taking office, but even not counting this time off, he has missed over 17% of voting days.

John Fetterman is a young, freshman Senator. He should be the picture of activism in Congress. Instead, he chronically misses votes, even when not counting the health episode at the beginning of his term. A lot of his freshman peers aren’t having this issue, like Rep. Jackson (D-IL), who is roughly the same age and has only missed 3 days (1.4% absence rate).

As a bonus, here’s the same visualization for Rep. Ganger. Despite an ostensible descent into dementia, her record in 2023 was comparatively quite good.

Conclusion

Look, I understand that a lot of these noted absences happened for health reasons. I do not want to minimize how gut-wrenchingly difficult it is to live with a chronic illness. I don’t talk about it a lot, but I also suffer from a chronic illness that took me out of the workforce for almost two years. So believe me, I am more sympathetic than the tone of this article perhaps implies. But I am also aware of my chronic illness and plan accordingly. I mean, I don’t even own a pet because I feel like it would be irresponsible. I have no delusions of grandeur that I’m fit to serve in Congress and oversee the well-being of hundreds of thousands of my fellow Americans.

We cannot be surprised that Kay Granger, an 81 year old woman, has dementia. Research indicates that more than 1 in 10 Americans over 65 has dementia. No one is forcing people this old to run for Congress. And no one is forcing someone with cancer to stay in Congress. Ultimately:

Our Congress owes it to us, their constituents, to show up to work. If they cannot do that, they should step down or not seek election in the first place.

As you might be able to tell, researching and writing this article made me mad. The blatant hypocrisy of many of these same members calling out the average American, specifically federal workers, for pushing for a right to work remotely shouldn’t be lost on us either. Congress should start by looking inwards, because the call is coming from inside the house.

Ultimately, working remotely is still working. Not showing up for Congressional votes, the most important part of your job, is not working at all. At the end of the day, we all deserve better from our elected representatives, regardless of our political beliefs.

Thanks for reading! As always, if you enjoyed this article and want to read more stuff like this please subscribe below.