Climate change has far reaching impacts beyond the gradual warming of the earth. The ocean is becoming more acidic, coral reefs are dying, and species are going extinct at alarming rates. In particular, extreme weather events appear to be becoming more common in recent years. Evidence suggests that severe floods and droughts have increased in certain regions of the United States. Anecdotally, just in the past few years, we’ve seen historic floods in Houston, the worst natural disaster in recorded history to hit Puerto Rico (Hurricane Maria), and devastating wildfires in Australia, just to name a few. I’m going to take a closer look and see if we can empirically show that flooding has gotten worse in frequency and magnitude in the Southern U.S. Interestingly, I found little scientific research on the subject. So basically. You heard it here first.

Flooding Down South

The Model

I obtained data from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) for the stream/river network for the American South. Particularly, I was interested in daily discharge, which is the quantity of water passing a location along a stream. A stream or river is only capable of handling so much discharge before overflow occurs, which results in flooding. As a result, discharge can be used as a metric of flooding severity. I restricted the streams I analyzed to the top 25th quartile by average yearly discharge, with the rationale that I was not interested in the “flooding” patterns of a small creek in rural Georgia. Note that because we only have data on streams, we cannot measure coastal flooding. So we are more specifically measuring stream flooding.

I then created a statistical model for each stream that modeled the average discharge trend over time, accounting for seasonal and yearly trends. In that way, I was able to account for the normal seasonal ebbs and flows that every river experiences (post-winter thaws, spring rains, etc.), as well as yearly trends (rivers growing or shrinking over time due to natural or human activity), or even the moderate flooding that is natural with some rivers, and zero in on truly extraordinary events — abnormal, or extreme floods. Below, you can see the result for the Mississippi River in Vicksburg, Mississippi from 2008 to 2011. Note that the model predicts some yearly spring flooding and that is taken into account in our “cutoff” so that the “regular floods” aren’t captured when we are counting extreme floods:

Notice that we appear to have some extreme flooding in 2011. Let’s zero in on that year:

Indeed, based on our cutoff, our model tells us there was a period of extreme flooding from May 8th until May 30th. Lo and behold if we look back in the news, there were major floods along the Mississippi River during April and May of 2011, substantiating our model!

Results

I used my model to check whether extreme floods were getting more frequent, as well as whether they were getting worse. There was statistically significant evidence that extreme floods got more frequent throughout the South, and results can be summarized below. If you live in a Southern state, you can select your state to see individualized results!

The picture is less clear for flood intensity. Although not statistically significant, in aggregate, there appears to be a slight positive trend in flood intensity over time (see above for the picture).

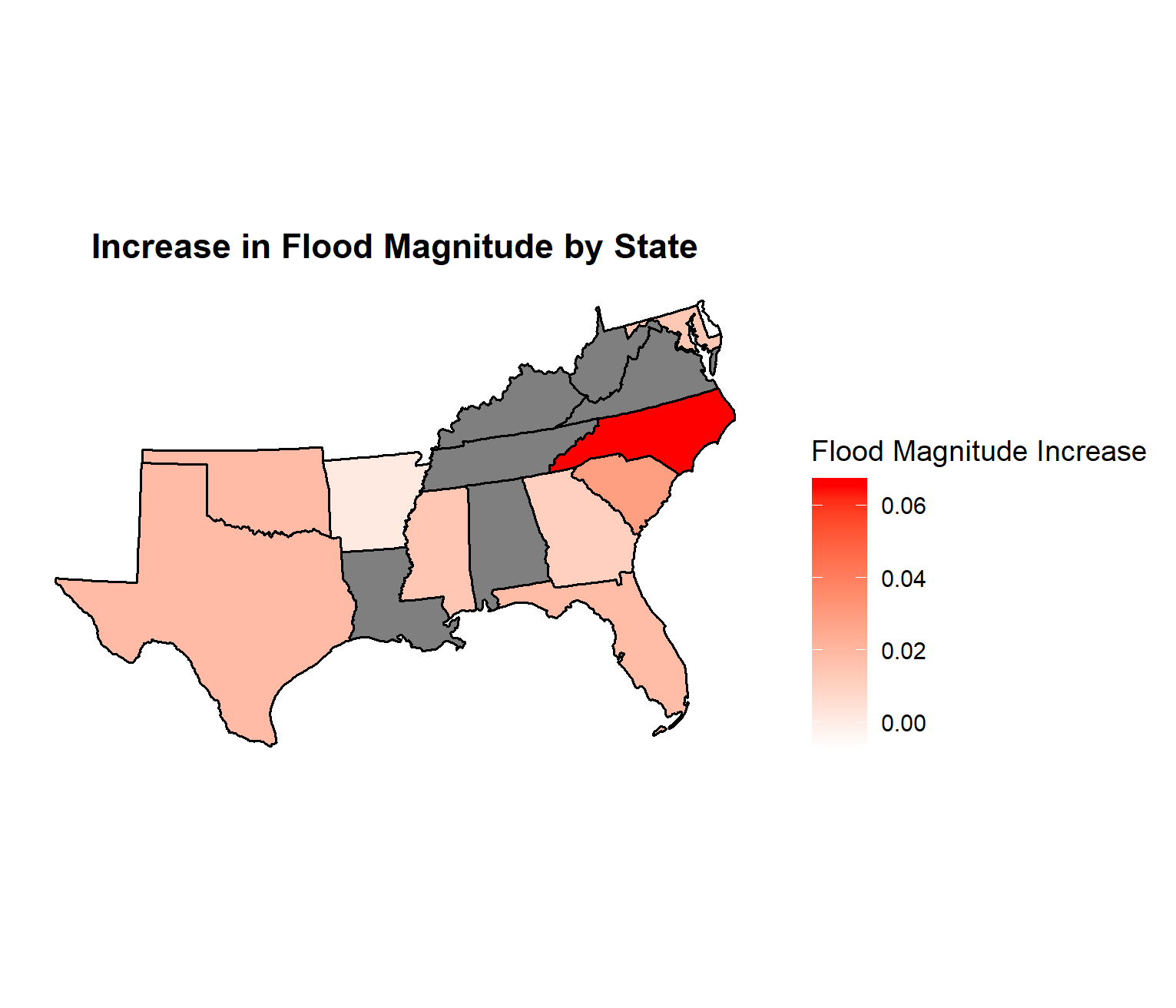

A heat map helps see where the increases are concentrated geographically — gray states have weak relationships between time and flood frequency and/or magnitude.

I’m obviously not a climatologist, so I can’t draw any conclusions as to why these increases are occurring. All I can say is that there is compelling statistical evidence that extreme flooding events are getting worse in the Southern United States. I’ll leave it up to you to draw your own conclusions as to why its happening.